Commentary: MLS made a colossal mistake to drop U.S. Open Cup. How does the league not get that?

Don Garber acknowledged long ago he didn’t know much about soccer when he left the NFL for MLS. Last week, the MLS commissioner showed he still doesn’t understand the sport.

The league’s attempt to limit its participation in the U.S. Open Cup to developmental MLS Next Pro players, knee-capping the country’s oldest national soccer competition, was a colossal mistake. And the league apparently knew it was courting controversy. Because while the decision was approved at the league’s board of governors gathering on Dec. 13, it wasn’t included in the news release that detailed the other mostly minor decisions made at the meeting.

Instead, MLS waited until Friday evening to make the announcement, hoping no one would notice.

U.S. Soccer, which manages the Open Cup, wasn’t warned the decision was coming even though Garber is a member of the federation’s board. One high-ranking federation employee said he found out about 15 minutes before leaving for the annual holiday party.

On Wednesday, five days after being blindsided, the federation denied the league’s attempted power play without elaboration. And U.S. Soccer appears to be on firm ground with the decision since one of the rules guiding its sanction of MLS as a first-division league requires that all “U.S.-based teams must participate in all representative U.S. Soccer and CONCACAF competitions for which they are eligible.”

That includes the U.S. Open Cup.

But the federation isn’t playing the heavy here, though. Although U.S. Soccer won’t allow the league to simply walk away from the tournament, it has indicated it is open to exploring ways to address Garber’s concerns and improve the competition. That will require some honest dialogue from the league.

MLS said its decision to replace first-team rosters with MLS Next Pro teams in the U.S. Open was an attempt to develop young professional players and provide them “with greater opportunity to play before fans in meaningful competition in a tournament setting” and to reduce schedule congestion.

That’s laughable. MLS’ developmental teams had that opportunity when they played in the second-tier USL Championship, but the league pulled out of that and formed the third-tier MLS Next Pro, over which it has control, in 2022.

Now it wants those teams to represent MLS in the U.S. Open Cup where they will play against — wait for it — USL Championship teams.

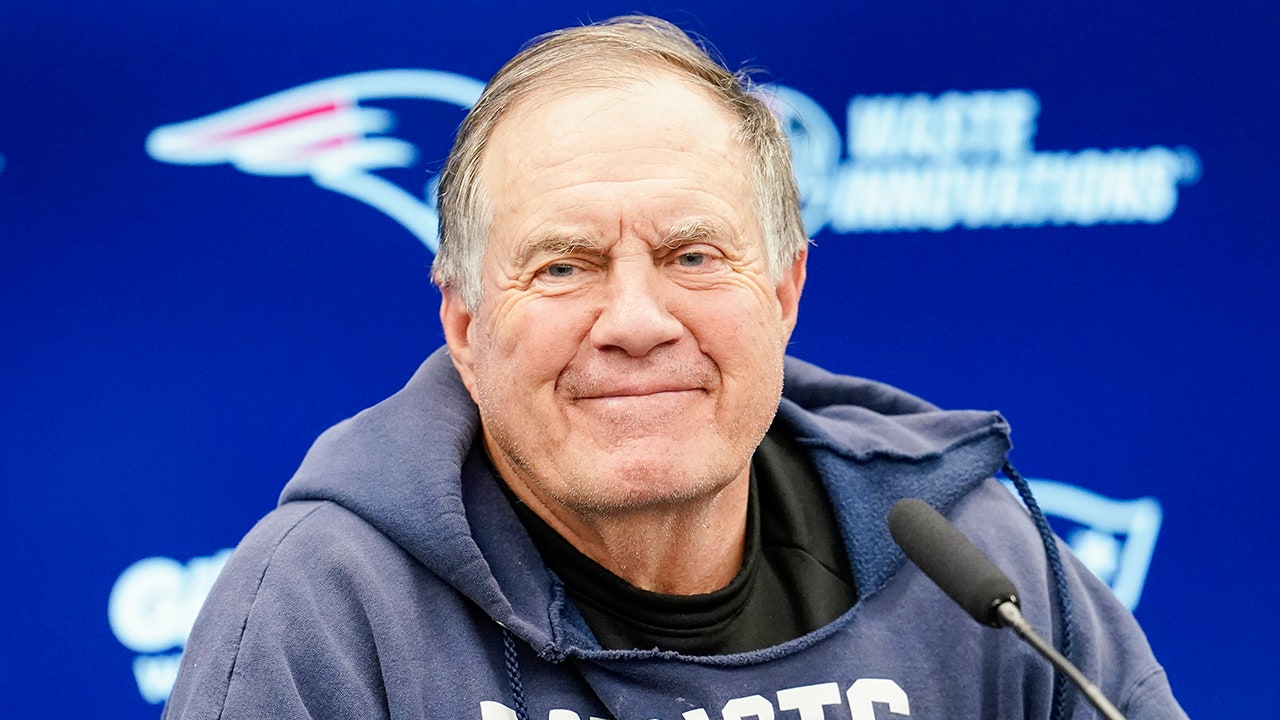

MLS Commissioner Don Garber speaks with reporters during MLS All-Star week.

(Alex Brandon / Associated Press)

As for the schedule congestion, that is wholly a product of the league’s hubris and overreach. Last summer, MLS added the Leagues Cup, a month-long 47-team tournament, to its calendar. Partly as a result, LAFC played a league-record 53 times in 41 weeks, participating in the MLS regular season and playoffs, the U.S. Open Cup, the Leagues Cup, the CONCACAF Champions League and Campeones Cup.

The recent addition of competitions with the Mexican league — Campeones Cup was created in 2018 — has done more to crowd the schedule than the U.S. Open Cup, which was here more than eight decades before MLS. But those newer tournaments feed Garber’s obsession with tapping into the Mexican fan base on both sides of the border, even if it means LAFC’s five games against Liga MX teams last season nearly matched the number of regular-season matches it played against the Eastern Conference of MLS.

The more likely motives behind the league’s attempt to pull out of the U.S. Open Cup were cash and control, essentially two sides of the same coin.

Last season was the first in the league’s 10-year, $2.5-billion broadcasting deal with Apple. But U.S. Soccer, not MLS or Apple, handles the marketing of the U.S. Open Cup and it sold the international rights to the event to Sportfive, a global marketing agency, while CBS Sports remains the domestic broadcaster, leaving Apple out in the cold. That’s why the Apple docuseries “Messi Meets America,” detailing Lionel Messi’s first season in MLS, did not include any footage from his team’s run to the Open Cup final.

Garber telegraphed his feelings about the Open Cup at a federation board meeting last spring when he called the tournament “a very poor reflection on what it is that we’re trying to do with soccer at the highest level.” His real disenchantment likely stemmed from the fact it was the only tournament that MLS had no control over and made little profit from.

As a business decision, Garber’s attempted move was unquestionably the right one. The league is healthier than it’s ever been and Garber, who joined MLS in 1999 when it was teetering on the edge of bankruptcy, deserves much of the credit for that. Including the playoffs, MLS drew nearly 12 million fans last season, with the addition of Messi bringing interest and attention from all over the world. Already the largest major first-division league in the world, it will add a 30th franchise in 2025, collecting a $500-million expansion fee .

Keeping Apple happy is far more important in continuing that growth than propping up the U.S. Open Cup. But the commissioner completely misread the room when he tried to push through changes to country’s oldest tournament by fiat.

In soccer, supporters aren’t simply fans of the sport. They are the sport. They create the culture, buy the tickets, collect the merchandise and attend the games — or don’t attend them, with the soccer website Transfermarkt putting the average attendance at U.S. Open Cup games last season at 5,477.

Tradition and popularity aren’t the same thing, however.

It’s traditional to have the Detroit Lions play a nationally televised game on Thanksgiving, for example. But no one watches the Lions the rest of the year. It’s the tradition we honor, not the game.

History works the same way. The 1927 Yankees are venerated as the greatest team of all-time, yet the Bronx Bombers’ average attendance that season was just 15,117. Jackie Robinson’s big-league debut changed baseball forever, but that game was played before nearly 8,000 empty seats.

None of the first three Super Bowls sold out.

Which is not to equate the U.S. Open Cup to the Super Bowl. Rather it’s to point out the tradition and history that sprang from many of the most iconic moments in sports had nothing to do with the crowd or the TV audience. The foundation of a building isn’t the most glamorous part of the architecture, but it is the most important.

The Open Cup is part of U.S. soccer’s architecture, whether anybody goes to the games or not. And by taking a jackhammer to that foundation, Garber threatened the integrity of the entire structure.

“They’ve completely lost the plot,” one fan wrote on social media. “The reason so many Americans love English soccer, and don’t pay attention to MLS, is the history. #USopenCup is the history of American soccer. How can they grow the game while leaving it behind?”