Column: Excited about AI and self-driving cars? A top roboticist is here to burst your bubble

If you’re a fan of techno-hype, 2023 was the year for you.

Believers felt themselves validated by seeing excitement and fear about AI chatbots reach previously untouched heights. Skeptics may have felt initially confounded by the rollout of driverless robotaxis in San Francisco and a few other cities, but ultimately validated when they were ordered off the streets by authorities concerned at their tendency to create traffic jams, interfere with emergency responses, and injure the occasional bystander.

Everyone else was probably confused by the relentless promises by commercial tech promoters that we were standing on the doorstep of a new world.

Get your thick coats now. There may be yet another AI winter, and perhaps even a full scale tech winter, just around the corner. And it is going to be cold.

— Rodney Brooks

Rodney Brooks is here to put it all in perspective, with his sixth annual Predictions Scorecard.

As he wrote in issuing the scorecard Jan. 1, this is his “sixth annual update on how [his] dated predictions from January 1st, 2018 concerning (1) self driving cars, (2) robotics, AI , and machine learning, and (3) human space travel, have held up.”

Long story short: They’ve held up very well.

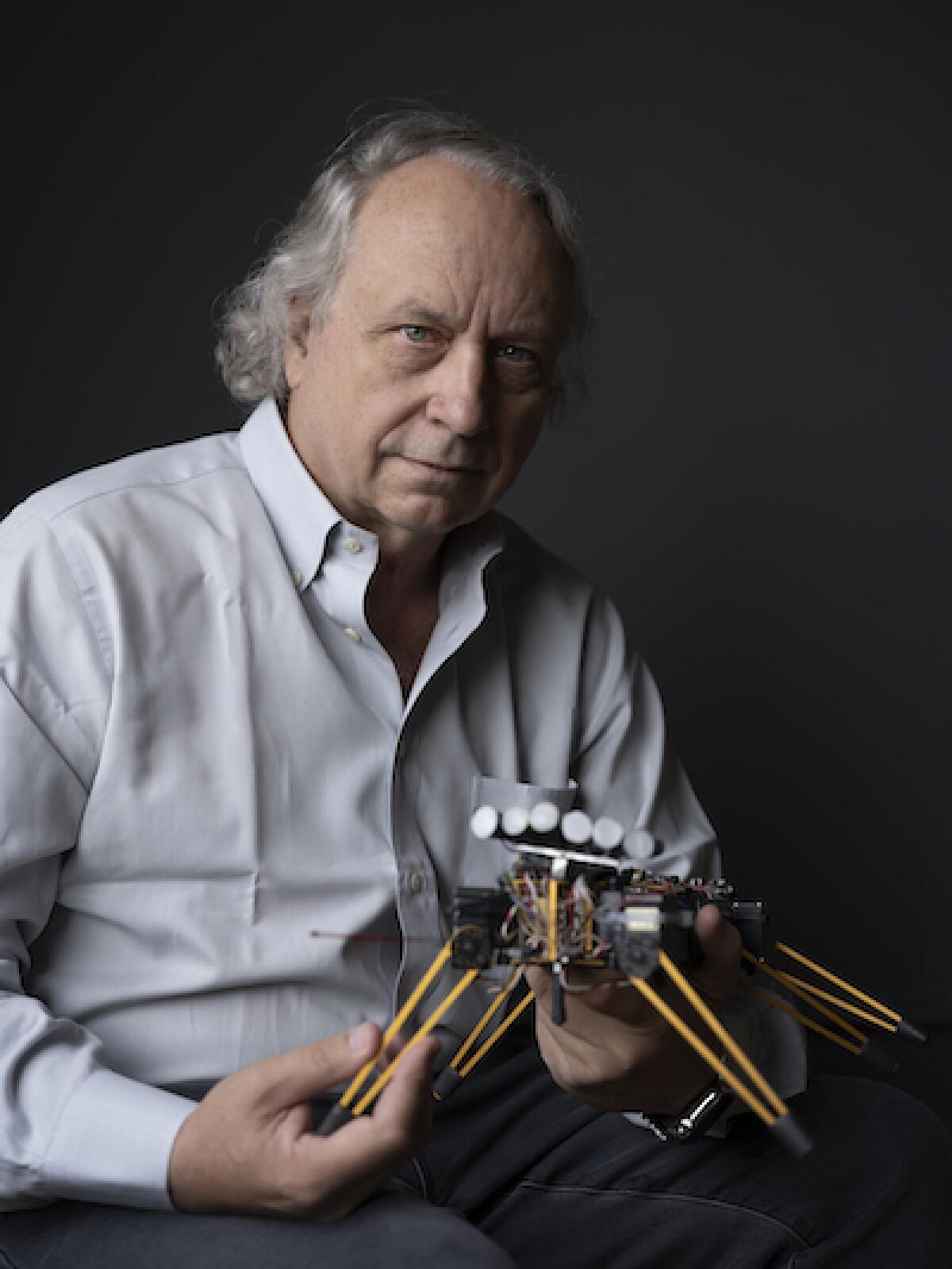

Why should we care what Brooks thinks? As I wrote a year ago in reporting on his fifth annual scorecard, Brooks is “one of the world’s most accomplished experts in robotics and artificial intelligence … a co-founder of IRobot, the maker of the Roomba robotic vacuum cleaner; co-founder and chief technology officer of RobustAI, which makes robots for factories and warehouses; and former director of computer and artificial intelligence labs at MIT.”

In other words, he’s the opposite of a Luddite. On the contrary, Brooks is deeply involved in technology research and development, but sufficiently independent-minded to call out hype where he sees it. He sees it a lot.

He is also a hands-on technology analyst. During 2023, he writes, he took almost 40 rides in Cruise robotaxis in San Francisco and wrote several blog posts about the experience.

On the whole, he found them less flexible or expedient than Lyft or Uber; the cars wouldn’t service his street and they were delayed or the rides canceled more often than the ride-hailing services.

He witnessed some decidedly dangerous behavior by the vehicles that would not have happened with human drivers, and on one occasion the Cruise in which he was riding froze in the middle of an intersection right in the path of an oncoming vehicle, to the point where Brooks was convinced he was about to be the victim of a violent collision. Luckily, the other driver slowed down, averting the accident.

“I have spent my whole professional life developing robots and my companies have built more of them than anyone else,” he writes in his scorecard, “but I can assure you that as a driver in San Francisco during the day I was getting pretty frustrated with driverless Cruise and Waymo vehicles doing stupid things that I saw and experienced every day.”

Rodney Brooks

(Christopher P. Michel)

Brooks pigeonholed his original 2018 predictions into three categories: technological advances projected to happen by a given date; those he expected to happen no earlier than a given date; and those he projects to happen “not in my lifetime” or “NIML” — meaning not before 2050, when he will have turned 95.

Since then, he has scored his and others’ predictions against those yardsticks. On the whole, Elon Musk’s 2015 prediction that the first fully autonomous Tesla would appear in 2018 and be approved by regulators by 2021, for example, gets a failing grade on both counts, since neither happened within the predicted time frame.

Let’s take a look at some of Brooks’ other scores.

Self-driving and electric cars take up the largest share of Brooks’ 2024 scorecard. In part, that’s because the technologies have occupied so much public mind space: When he first issued his dated predictions, he writes, “the hubris about the coming of self driving cars was at a similar level to the hubris in 2023 about ChatGPT being a step towards AGI (Artificial General Intelligence) being just around the corner.”

The focus then was on the advent of Level 4 autonomy, in which the car can do everything though human override is still possible and occasionally required; and Level 5, in which no human interaction is needed. Through 2017, car manufacturers, autonomous systems developers and ride-hailing firms such as Uber were predicting that self-driving cars would be available no later than 2022.

As of now, Brooks notes, “there are no self driving cars deployed (despite what companies have tried to project to make it seem it has happened).” The prospects for robotaxis, he adds, “took a beating” in 2023, with Cruise robotaxis being ordered off the streets. General Motors, the owner of Cruise, appears to be growing disenchanted with the enterprise after having poured billions of dollars into it; Cruise chief executive and co-founder Kyle Vogt resigned in November.

Meanwhile, Waymo, the leading Cruise competitor, is a money pit for its owner, Alphabet. As for Tesla, where Musk constantly issues torrents of hype about self-driving being already achieved, if you believe anything Musk says on any topic, that’s your problem.

Brooks is a believer in electric cars; he owns one and says he loves it. But he is also fully alive to the obstacles still confronting their market growth. Many people even in affluent neighborhoods have no access to private parking spaces where they can charge up day or night.

“Having an electric car is an incredible time tax on people who do not have their own parking spot with access to electricity,” Brooks observes. That’s one reason that EV sales are plateauing, except in pockets such as West Coast cities and Washington, D.C. At this moment, the future of the electric car rollout appears to be in hybrids, which will run on electricity or gasoline.

Then there’s artificial intelligence, a field with which Brooks is intimately familiar and that he watches very carefully.

He is especially wary of the public’s tendency to project contemporary claims ahead to the science fiction of robots taking over the Earth.

He doesn’t expect to see “a robot that seems as intelligent, as attentive, and as faithful as a dog” before 2048. “This is so much harder than most people imagine it to be,” he writes. “Many think we are already there; I say we are not at all there.”

And “a robot that has any real idea about its own existence, or the existence of humans in the way that a six year old understands humans”? Not in his lifetime.

Brooks predicted in 2018 that the “next big thing” in AI beyond deep learning, which was what the field had reached by then, would emerge between 2023 and 2027, though he did not know what it would be.

It happened in 2023, with the emergence of large language models, or LLMs — the ChatGPT-style chatbots that have consumed the attention of the entrepreneurial world and the popular press over the last year.

In his writings and a talk he gave at MIT in November, Brooks has been “encouraging people to do good things with LLMs but to not believe the conceit that their existence means we are on the verge of Artificial General Intelligence.”

But he takes the long view of AI — not merely looking ahead, but looking back at AI’s past. The field, he writes, is “following a well worn hype cycle that we have seen again, and again, during the 60+ year history of AI.”

The lesson that Brooks strives to leave us with is that technological progress almost always takes longer than we expect — the last mile in research and development may look like a trivial challenge, given the accomplishments that preceded it. But it’s often the most difficult part of the path to traverse.

Moreover, the progress of a new technology can often be mapped as peaks of achievement interspersed with troughs of disappointment and disaffection.

“Get your thick coats now,” he concludes. “There may be yet another AI winter, and perhaps even a full scale tech winter, just around the corner. And it is going to be cold.”