Giovani Giuria’s journey from homelessness to amateur soccer announcer occurred in one Van Nuys park

Giovani Giuria’s pregame preparation is meticulous. There’s no press box, no roster program and no pregame stats. On most nights, he’s a one-man show. Just a tablet, a tripod, a camera and his voice.

The whistle blows and Giuria’s livestream begins. He narrates every threatening moment at an amateur soccer match at West Adams High School attended by hundreds. The match is part of Liga Morazan, an amateur soccer league based in L.A. County. Minutes before halftime, the 0-0 deadlock is broken.

“Cuidado! Se viene en el area. … Dispara al arcoooooo,” Giuria exclaimed via his livestream of the championship doubleheader.

Giuria’s voice crescendos and reverberates — 1-0 to San Pedro FC.

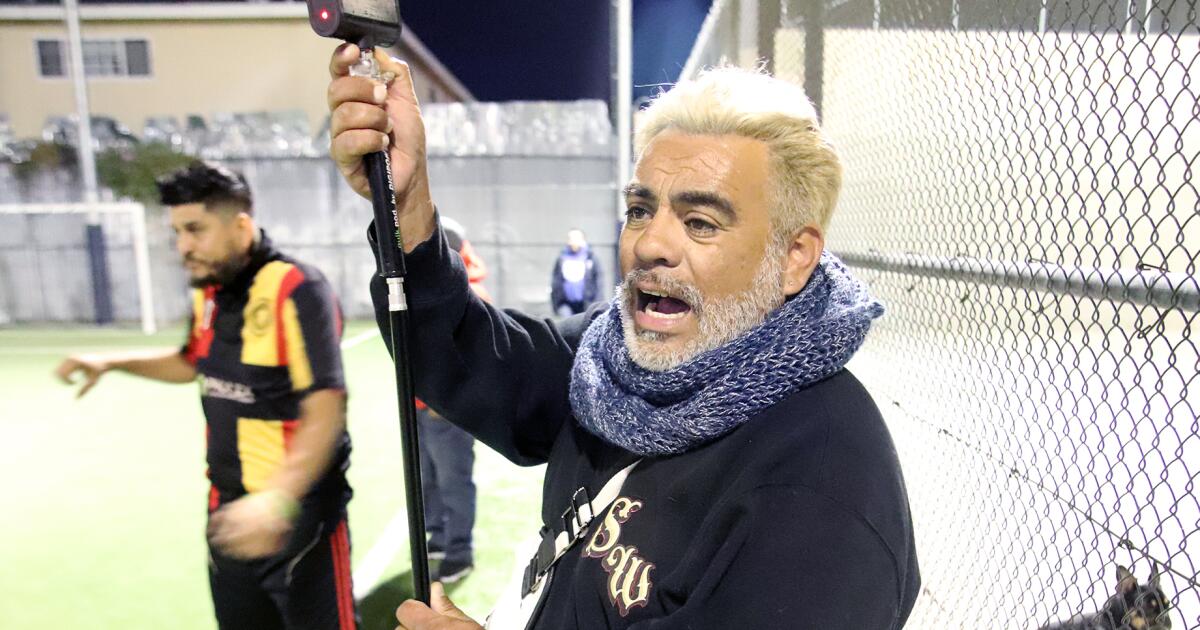

Giovani Giuria holds his tripod as he comments on a soccer game for his YouTube channel, Gio Sport.

(James Carbone / For De Los)

“Goooool. Gooool. Gooool.”

Giuria’s opening goal call is followed by four more. The match ends in a 3-2 San Pedro FC victory over Club Garrafones and the awarding of a $7,000 grand prize. Giuria makes his way down onto the field, navigating the sea of jubilant faces and hung heads, preparing for the second championship match. He darts to every player, jotting down their first and last names and corresponding jersey number.

For Giuria — more commonly known in the Los Angeles soccer community by his YouTube handle, Gio Sport — this isn’t a hobby. It’s Giuria’s livelihood.

He has spent the last seven years making a living calling amateur soccer games, accumulating more than 8,000 subscribers and uploading more than 4,000 videos to his YouTube channel.

Giovani Giuria greets a soccer player before a local club game.

(James Carbone / For De Los)

Giuria’s following stems not from his state-of-the-art video production stream, but rather how he chronicles the match’s flow, his cadence leading up to the climatic moments.

“Everyone loves [Giuria’s] narration,” Cristobal Acevedo, a Van Nuys soccer league director, said in Spanish. “When I first saw him, [his voice] surprised me. He sounds like a professional [commentator] and it grabs your attention.”

Giuria’s style can be traced back to when he was 13 years old in Peru and his older brother gifted him a radio before leaving for the United States. Giuria spent hours listening to a 24-hour sports radio station that played games of Peru’s top-flight domestic soccer league.

The sports radio station became his muse. He soaked up the commentators’ every word, inflection and tone. Even late into the night, the radio station played old games as Giuria fell asleep, subconsciously developing the foundation of his craft.

“I believe it stuck with me in my dreams,” Giuria said in Spanish. “I believe this type of therapy was important. … And it built this confidence that made commentating so easy for me. Narrating is as natural as breathing for me.”

The radio planted a seed that blossomed into Giuria pursuing a degree in journalism at the Universidad de San Martín de Porres in Lima, Peru.

Giovani Giuria comments on the Pumas vs. Morellos match for his YouTube channel.

(James Carbone / For De Los)

But it still took some years into his journalism career before he found his true passion — calling soccer games. His first opportunity came in 2003 at the Estadio Max Augustín in Peru, where called a game live on the radio between Club Deportivo Sport Loreto and L.D.U. Quito.

He spent the next seven years calling games before he decided to immigrate to the United States with his son in 2011. Giuria found jobs working at various car dealerships throughout the San Fernando Valley.

But Giuria’s life changed drastically in 2015, when his driver’s license was suspended. He said he unknowingly had accrued $2,800 in unpaid tickets when his then-girlfriend did not tell him she had accumulated the violations while borrowing Giuria’s car. The suspension ultimately led to Giuria’s dismissal from his job, which required a valid license.

He fell into homelessness and lived in his van for several months. He found refuge in the corner parking spot of the Van Nuys Recreation Center’s small parking lot. The park, at the time, was home to a dirt soccer field and futsal court.

It was there that Giuria met Rita Vasquez, a recreation assistant for the city of Los Angeles. Vasquez noticed Giuria parked in the same spot nearly every day she came in to work. The two eventually became friends.

Vasquez said “out of respect,” the two never talked about Giuria’s homelessness, but Vasquez was there to buy him dinner nearly every weekend, knowing he’d reciprocate if the roles were reversed.

Vasquez remembered she would often hear him say, “I’m going to do something. I just don’t know what.”

One day, Giuria realized what that something was — Gio Sport. Giuria used what little money he had and convinced T-Mobile to overlook his credit and allow him to finance a tablet, he said. With the tablet and his newly created Gio Sport YouTube channel, he began streaming and calling games at the Van Nuys Recreation Center.

Eventually, enough teams and leagues throughout Southern California sought his services that he no longer had to live in his van.

“To be great at something, it’s not made. You’re born with it,” Vasquez said of Giuria’s success. “It gives me great pleasure to see how far he’s come.”

As Giuria’s popularity grew and he became a fixture around more prominent amateur adult leagues, so did the number of encounters with grateful Gio Sport followers, who thanked him for providing a platform for relatives outside the U.S. to see their loved ones play.

“It makes my work so meaningful and when the [community] is giving from the heart, you’re blessed,” Giuria said. “And after my death, I will live for 100 more years because of all the people who’ve watched my videos and have enjoyed watching their loved ones’ games.”

Jorge Ramos is a freelance writer covering prep sports and soccer in Los Angeles. He previously covered prep sports in Southeast Texas. He is an Arizona State University graduate and a San Gabriel Valley native.