Ignacio E. Lozano Jr., longtime La Opinión publisher, dies at 96

Ignacio E. Lozano Jr. loved to tell the story about arriving in Los Angeles in 1948 from the University of Notre Dame with a journalism degree, taking a look at his family’s business — and immediately fearing it was doomed.

His father, Ignacio E. Lozano Sr., was a pioneering publisher who founded a Spanish-language daily in San Antonio before launching La Opinión in Los Angeles on Mexican Independence Day in 1926. His broadsheet quickly earned a following in L.A. and beyond by serving as a portal back home to the hundreds of thousands of Mexican immigrants who, like him, had fled their country’s political chaos and settled in Southern California.

Lozano Jr. became associate publisher under his father, then at the age of 27 succeeded him as publisher after the elder Lozano died of cancer. The way the young heir saw it, though, La Opinión’s days were numbered. Mexican migration to the United States had slowed, and second-generation Mexicans didn’t seem to crave the same news their parents did.

“The Mexican-American would be totally assimilated into the community,” Lozano told The Times in 1976. “They would no longer speak, much less read, Spanish.”

Fortunately for the family business, he was wrong.

Lozano died Wednesday in Los Angeles of age-related complications. He was 96.

In the decades after his serendipitously erroneous prediction, migration from Latin America radically transformed Los Angeles and made Spanish the city’s second language. La Opinión under Lozano expanded from focusing largely on foreign news to covering local issues important to Latinos that the English-language media either ignored or grossly misinterpreted.

As La Opinión’s influence spread and Latino migration continued, government officials sought Lozano’s counsel. He was named a consultant to the U.S. State Department by President Lyndon Johnson, was appointed to the Council of the Californias by then-Gov. Ronald Reagan, and joined President Richard Nixon’s Advisory Council on Spanish-Speaking Americans.

His political rise reached an apogee in 1976, when President Gerald Ford appointed Lozano as U.S. ambassador to El Salvador. He and his wife embarked to the Central American country, leaving La Opinión in the hands of their son and daughter, Jose Ignacio and Leticia.

Lozano stayed in that position for only nine months, but what he saw profoundly affected him. Catholic priests and liberal government officials were being kidnapped and murdered with impunity, and the American Embassy had to deal with increasing requests for asylum from people afraid that they might be next.

He warned a House subcommittee in 1977 about the “campaign of vilification” the Salvadoran government was waging against the Roman Catholic Church, which would culminate three years later in the assassination of Archbishop Óscar Romero, whom Lozano knew personally.

After stepping down as ambassador, Lozano returned to La Opinión. He knew Los Angeles would receive an unprecedented influx of refugees from Central America, and asked his staff to be ready.

“He allowed me to do the journalism that I wanted to do and we needed to do,” said J. Gerardo López, who joined La Opinión as a reporter in 1977 and worked there for 27 years, the last nine as executive editor. When López one day remarked offhandedly to Lozano — whom he affectionately referred to as mi gran jefazo (my big boss-man) — that congressional hearings on immigration were about to start, Lozano told him to get on a plane to Washington, D.C. By then, La Opinión was one of the largest Spanish-language newspapers in the United States.

“That type of confidence — who gives it to you?” said López. “It wasn’t necessary to talk to him about issues or stories — they gushed out of him.”

In 2006, after receiving a lifetime achievement award from the newspaper El País in Madrid to mark La Opinión’s 80th anniversary, Lozano said in an interview with the paper he’d since retired from: “The interests of a businessman aren’t always the same of the community in general. But in the case of our family and [newspaper], I believe that our interests coincided with those of all the Hispanic community.”

“He saw that ahead of others,” said retired USC journalism professor Félix Gutiérrez, who got to know Lozano in the 1980s. “He was aware of the impact of, the importance of, what he was doing and the community that he was serving.”

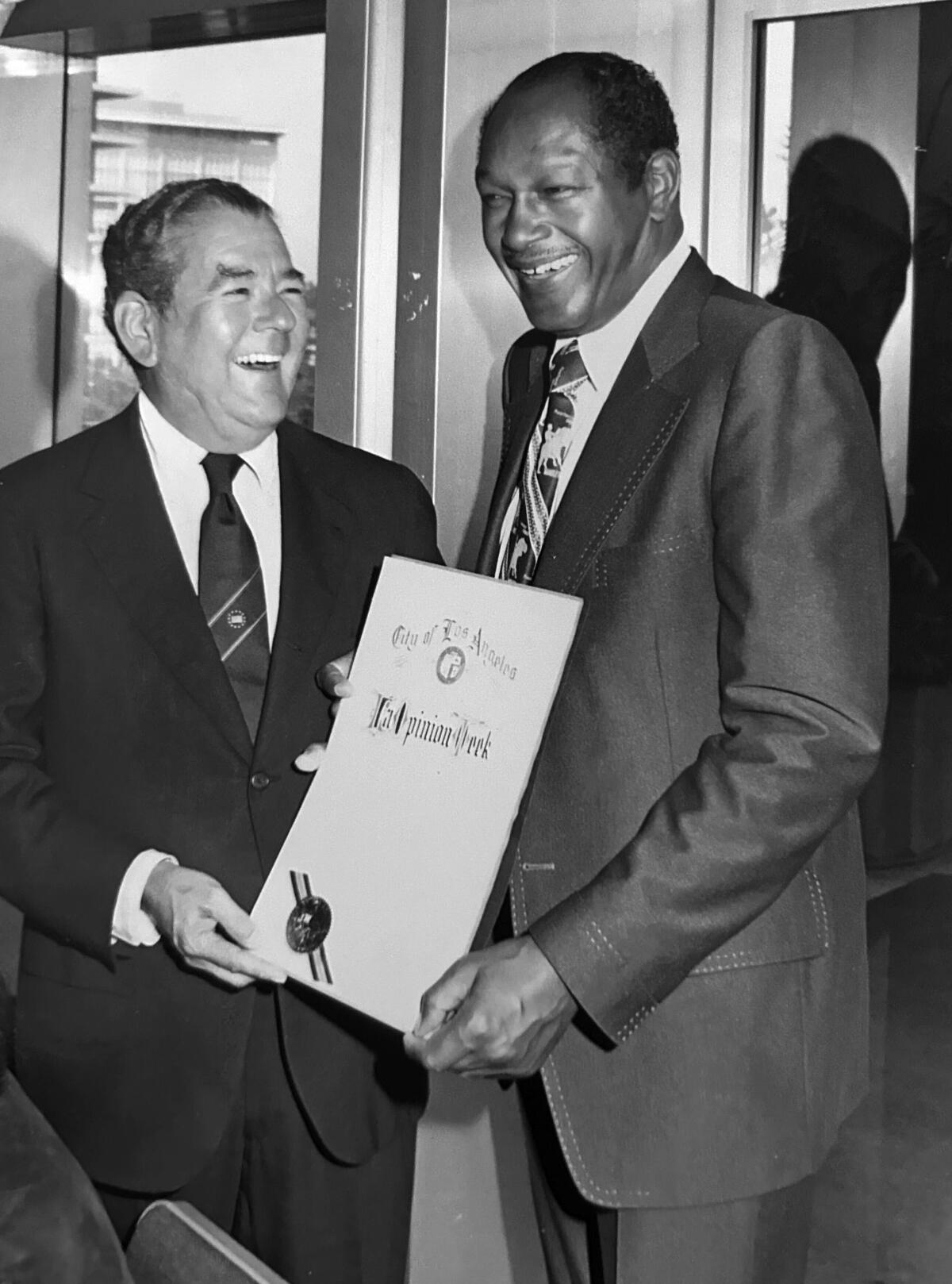

Former Los Angeles Mayor Tom Bradley with Ignacio E. Lozano Jr., who was a major player in L.A. and beyond.

(Courtesy of Monica Lozano)

“Dad understood that our community needed a vehicle that could represent their voice, their interests and also communicate to the broader audience in Los Angeles the incredible contributions that we were making,” said Monica Cecilia Lozano, his daughter. She, like her three siblings, followed in their father’s path to work at La Opinión and its parent company, ImpreMedia.

Lozano stepped down as publisher in 1986, handing the position to son Jose Ignacio — but Lozano’s influence was just beginning. He sat on corporate boards where he was frequently the only Latino in the room, including for Bank of America, Walt Disney Co., National Public Radio and his alma mater. He advised CEOs and community leaders alike, and cheered on as his children took La Opinión into the digital age and covered the continued rise of Latinos in L.A. and beyond.

“He was wealthy, he was well-liked, but he never, never forgot the people who bought his newspapers and whom he sought to represent,” said Antonia Hernández, former president of the Mexican American Legal Defense and Educational Fund as well as the California Community Foundation, nonprofits on whose boards Lozano sat. “He was the epitome of corporate business success and having pride in being Mexican American.”

Young people, Hernández continued, “say that’s no big thing. Hell, when you’re from a community where no one pays attention to you and treats you as insignificant, that’s a hell of a lot.”

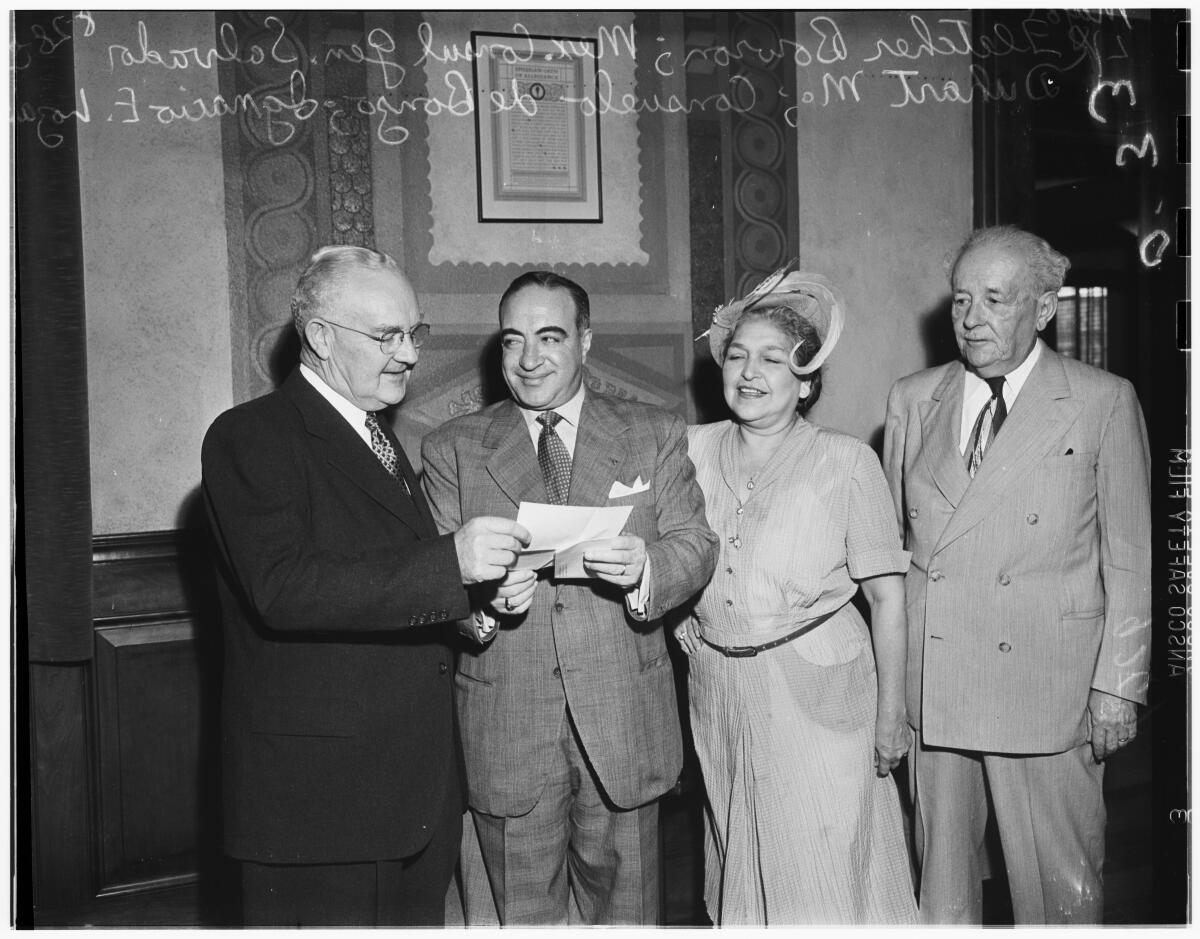

La Opinión founder Ignacio E. Lozano Sr., right, joins then-L.A. Mayor Fletcher Bowron, left, and others in 1951 to discuss plans for Mexican Independence Day, which the paper hosted celebrations for in conjunction with its anniversary.

(University of Southern California / Corbis via Getty Images)

Ignacio Eugenio Lozano Jr. was born in San Antonio in 1926, the same year his father debuted La Opinión. The son was raised in the Alamo City until he left for college. When he arrived in Los Angeles, Ignacio Jr. told his father he would never return to their hometown.

Ignacio Sr. instilled in his son early on the philosophy that he told The Times in 1987 his paper tried to live up to every day: “Being honest with our readers. Playing it straight in our dealings with the political world, not allowing influence by our advertisers, trying to present the news as honestly as we can.”

In 1953, Lozano Jr. took over a newspaper with a new printing plant, a circulation of 12,000 and existential challenges. The paper under his father had covered local issues overlooked or vilified by L.A.’s English-language newspapers, like the forced deportations of Mexican and American citizens during the 1930s, the Zoot Suit Riots in 1943, and the 1949 election of Edward Roybal, the first Latino member of the L.A. City Council since the 19th century. But La Opinión was still mostly oriented toward Mexico.

Circulation growth had slowed. Competition emerged with Spanish-language radio and the debut of television station KMEX Channel 34 in 1962. The younger Lozano decided he needed to reorient his paper to focus on L.A.

“It is no longer a Mexican newspaper published in Los Angeles,” he told The Times in 1976, “but an American newspaper which happens to be published in Spanish.”

He hired more reporters, expanded coverage into Orange County, and urged his writers to find stories and issues that would explain Southern California and the United States to the Latin Americans who were coming in increasing numbers to the region after the loosening of immigration laws in 1965.

“He started thinking about the newspaper as not just a newspaper, but as a spotlight on the community as an entity in itself,” said Jose Ignacio Lozano, who began working in the printing press in high school and eventually left college to work alongside his dad full time after Lozano told him the best way to impact Latinos was “by running this newspaper.”

“People would read it and they would pass it along,” said Gutiérrez, the USC professor, who was part of the underground Chicano press in the late 1960s, a scene that La Opinión covered. “It wasn’t a read-and-toss-it type of paper.”

La Opinión’s success made Lozano one of the wealthiest Latinos in the United States — he liked to commute in his Porsche from his Lido Isle home to his paper’s downtown L.A. offices. It also made him Los Angeles royalty. For decades, his family hosted luncheons at the Dorothy Chandler Pavilion attended by the city’s political and Latino elite to simultaneously celebrate La Opinión’s anniversary and Mexican Independence Day. He golfed in Scotland, belonged to the Newport Beach Yacht Club, and flew his plane to tailgate at Notre Dame before football games.

At home, Lozano required that his children speak only Spanish and be proud of their Mexican roots in then ultra-white Orange County. He also pushed them to follow his lead — not just professionally, but by giving back to Latinos.

His philanthropic interests included the Boy Scouts, college scholarships at his alma mater, and the world of theater; while on the board of directors of South Coast Repertory, Lozano successfully pushed for the Hispanic Playwrights Project to help Latino writers develop works, an innovative program that was the first of its kind in the U.S.

“I’ve been ‘the Latino’ on enough mainstream community organizations,” Lozano told the Times in 1987. “It’s time I devoted more attention to things that interest me as a Latino, things that show an interest in the Latino community and culture.”

His noblesse oblige masked a steely newsman who stood by his publication and industry whenever they were under attack.

Lozano was deeply shaken by the 1970 killing of his friend Ruben Salazar as the Los Angeles Times columnist was covering the Chicano Moratorium in East Los Angeles. The following year, La Opinión’s front office was bombed as part of a string of explosions at Spanish-language media entities that Los Angeles police never solved.

Left-leaning activists would complain that the paper was too conservative and was missing important stories. Lozano once invited them into his office so they could let him have it. He heard them out, then went through the clippings they had brought and calmly showed where they were wrong. With nothing to say in response, the activists left.

Lozano served for years as head of the Inter American Press Assn., which advocates for a free press across Latin America. “When you look at the ways some of our colleagues have to live in other parts of the world, you give thanks to God and to the U.S. Constitution,” he told The Times in 1978.

That belief was tested in 1981, when La Opinión photographer Octavio Gomez told his bosses that Immigration and Naturalization Service agents had intimidated and assaulted him as he covered anti-deportation protests.

The paper complained to the local U.S. district attorney’s office, and when immigration officials denied the allegations and said their agents were just doing their job, Lozano sued the agency. In 1985, U.S. District Court Judge Mariana R. Pfaelzer awarded Gomez and La Opinión $300,000 and described the behavior of the immigration agents as “outrageous and … intentional.”

“While we appreciate the damages that were awarded, the most important thing in this case was the principle,” Lozano told The Times. “We do not want our [reporters and photographers] to be intimidated by immigration officials.”

By the time Lozano stepped down as publisher the following year, La Opinión’s circulation had increased to 70,000. He remained on the governing board of the paper for a few years, and engineered a 50-50 partnership in 1990 with the Los Angeles Times’ parent company that allowed his family to maintain editorial oversight.

While he no longer had a day-to-day involvement in the paper after his retirement, Lozano’s example of advocating for Latinos via reporting always loomed large for La Opinión staff and leadership. It proved especially influential in 1994, when anti-immigrant sentiment stoked by Republican leaders led to the passage of Proposition 187, which sought to make life miserable for undocumented immigrants. La Opinión aggressively covered the ballot initiative and the movement against it. The coverage pleased the patriarch, who left the GOP.

“I thought it was time for us to help our readers become active citizens, those who weren’t citizens to become citizens, and those who were citizens to register to vote and become part of the community, calling their own shots for what was best for them,” Lozano said of the coverage, speaking in a documentary made for the 90th anniversary of La Opinión.

But by then, the Lozanos were no longer involved in the paper. They had taken back full control of La Opinión in 2004, then merged with El Diario/La Prensa in New York with plans for a Spanish-language news empire. Circulation reached about 125,000. But the vicissitudes of journalism in the online era caught up with the family. A Argentine newspaper bought a controlling interest in ImpreMedia in 2012 and took it over outright in 2016.

The day that happened, Monica Lozano went to her dad to break the news, expecting to hear his disappointment. “He told me, ‘Monica, it is extraordinary that in this day and age, it has been family-held and -operated for as long as it has. To do what we have done for as long as we had done is extremely meaningful. Be proud of that legacy.’”

Lozano was preceded in death in 2018 by Marta Navarro Lozano, his wife of 67 years. He is survived by his daughters Monica Cecilia Lozano and Leticia Eugenia Lozano, his sons Jose Ignacio Lozano and Francisco Antonio Lozano, and nine grandchildren. A celebration of life is planned for sometime in 2024.