Teens struggle to identify misinformation about Israel-Hamas conflict — the world’s second “social media war”

Decimated neighborhoods. Injured children. Terrorized festivalgoers running for their lives. Since the brutal war between Israel and Hamas began nearly three months ago, Maddy Miller, a 17-year-old high school senior in Dallas, Texas, has been trying to make sense of the horrific scenes unfolding daily on her phone.

“I’ll just open TikTok or Instagram and it’s like, ‘here’s a clip from inside Israel or inside Palestine,'” Miller said. “Sometimes I just need to sit down for like 10 minutes and actually figure out what’s happening. It’s hard to know what’s real and what’s fake.”

In February 2022, the war in Ukraine began to play out on Tik Tok and Instagram. The conflict in the Middle East is now the second war to be viewed in vivid, and often intimate, vignettes on social media, where 51% of younger Gen Z teens get their news, according to a Deloitte survey. The war between Israel and Hamas has also sparked a tidal wave of misinformation and disinformation, which is reaching American teens like Miller.

In a packed classroom at Highland Park High School, Miller and about 30 other students study media literacy, a course many teens across the United States are not required to take. Texas is one of only four states in the U.S. that mandate a media literacy curriculum in all public schools beginning in kindergarten. Fourteen other states offer some form of media literacy education or online resources to public school students.

Media literacy classes

As part of every lesson, Brandon Jackson teaches students the tools needed to spot misinformation, which is false or misleading, and disinformation, which is deliberately deceptive. He also tests his students using real-world examples of fake videos that circulate on social media.

“The whole point of this is to analyze large international news events,” Jackson told his students. “How does information change when you’re looking at it on social media? Is it manipulative?”

Despite the technological edge young Americans have over older generations, Stanford University researchers Sam Wineburg and Joel Breakstone say teenagers’ ability to identify misinformation on social media is concerningly low.

“Video has a kind of immediacy, but we need to help people understand how to evaluate a video,” Wineburg said. “Is the person who’s providing the video an objective source? Does that person, are there reputational costs if that person is wrong, or are they some ‘rando’ that has sensationalist footage and is a rage merchant?”

Wineburg and Breakstone tested the ability of high schoolers to identify misinformation on social media. They chose more than 3,000 students, whose backgrounds reflected the demographics of the U.S., and asked them to determine whether or not an anonymous video was real or fake.

“The video purported to claim to show voter fraud in the United States,” Breakstone explained. “If you did a quick internet search, within 30 seconds you could discover that the video actually showed voter fraud in Russia. However, out of those more than 3,000 students, how many students actually discovered the link to Russia? Three. That’s less than one-tenth of 1%.”

The experiment

A CBS News investigation revealed how quickly mis- and disinformation is reaching teenage accounts on social media. In an experiment, a team of journalists set up three different profiles on Instagram and TikTok.

One account searched simple terms on Israel; another searched simple Palestinian terms; and the last account searched both. Each alias also followed several accounts with more than 1,000 followers and “liked” a handful of posts for each one.

While the faux-teen accounts were initially fed typical teenage content, like posts about getting ready for high school and makeup tutorials, on TikTok and Instagram, the algorithms also took into account the searches. Not long after the search terms were entered, each feed was flooded with war-related content, including misinformation.

TikTok

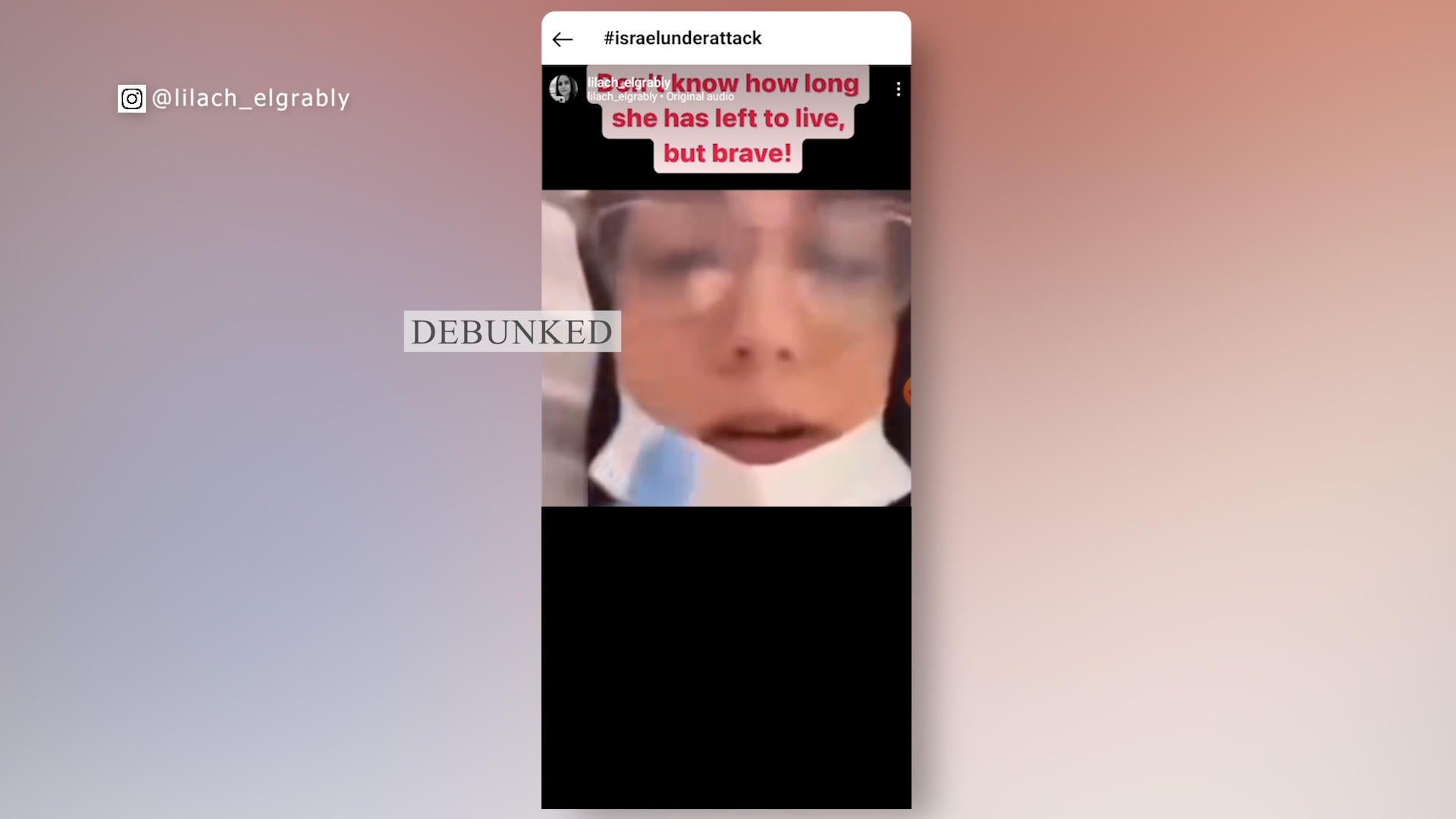

In one widely debunked video, a person, who claimed to work at a hospital in Gaza, alleged Hamas had overrun the facility. She said she had to perform surgery on a child without morphine. An analysis revealed the video was staged and even the explosions were manufactured. Another now-debunked video claimed to show an Iranian warplane landing on an Israeli aircraft carrier.

“It looks like a video game to me,” said Dan Evon at the News Literacy Project, a nonpartisan group that advocates for media literacy in schools.

Evon has spent his career deciphering fact from fiction on social media. He also teaches young people how to spot mis- and disinformation. Key to that is what he calls “pre-bunking”: equipping them with the tools to help identify misinformation before they fall for it.

“The same tip that I give every single time is to slow down,” said Evon. “Look for authenticity; look for the source; look for evidence; look for reasoning and to look for the context.”

“More dangerous paths”

From the highly publicized resignation of the president of the University of Pennsylvania, to high school walkouts in San Francisco and New York City, the war has undeniably created a tense climate in schools nationwide. Reports of antisemitic and Islamophobic threats and violence have soared.

“It doesn’t feel like we’re living in 2023. Feels like we’re living in Nazi Germany,” one student said.

Experts like Evon, Breakstone and Wineburg said false or misleading information can intensify the already heated debates about this conflict.

“When young people are developing their views about the world, false claims alter that,” Evon said. “They drag people down more dangerous paths.”

The students at Highland Park High School agree.

“It can just be really dangerous if we don’t seek out the real information,” Miller said. “I hope that people in our generation start to become more educated about issues.”

Response from TikTok

CBS News discussed the experiment findings with spokespeople from TikTok. After the team sent the company links to examples of misinformation, those posts were removed.

“TikTok works relentlessly to remove harmful misinformation, and partners with independent fact-checkers who assess the accuracy of content in more than 50 languages,” a TikTok spokesperson said. We’ve removed more than 131,000 videos for misinformation since the start of the Israel-Hamas war and direct people searching for content related to the conflict to Reuters.”

TikTok spokespeople also said:

- Our Community Guidelines are clear that we do not allow inaccurate, misleading, or false content that may cause significant harm to individuals or society, regardless of intent. We reviewed content sent to us by CBS and have removed those that violate our policies.

- We use a combination of technology and human moderation to enforce those guidelines, and we review content at multiple stages including initial upload, when content is reported to us and as it rises in popularity.

- We have over 40,000 talented safety professionals dedicated to keeping TikTok safe. We also rely on independent fact-checking partners and our database of previously fact-checked claims to help assess the accuracy of content. We work with 17 fact checking partners globally, who cover over 50 languages globally.

- We provide access to authoritative information at the very top of search to provide access to facts. For example, searching for “Israel” on TikTok directs people to resources from Reuters.

Response from Meta about Instagram

“We’ve taken significant steps to fight the spread of misinformation using a three-part strategy – remove content that violates our Community Standards, flag and reduce distribution of stories marked as false by third-party fact-checkers,” a Meta spokesperson said. “We also label content and inform people so they can decide what to read, trust and share.”

The Meta spokesperson also said:

- We’re working with third-party fact-checkers in the region to debunk false claims. Meta has the largest third-party fact checking network of any platform, with coverage in both Arabic and Hebrew, through AFP, Reuters and Fatabyyano. When they rate something as false, we move this content lower in Feed so fewer people see it.

- We recognize the importance of speed in moments like this, so we’ve made it easier for fact-checkers to find and rate content related to the war, using keyword detection to group related content in one place.

- We’re also giving people more information to decide what to read, trust, and share by adding warning labels on content rated false by third-party fact-checkers and applying labels to state-controlled media publishers.